Click on the images below to open the gallery and view them full-size.

Welcome to the fourteenth episode of the Global History Podcast. Today, we’d like to welcome Craig Lambert and Steven Mentz.

Craig Lambert is Associate Professor in Maritime History at the University of Southampton. In his own words, Dr. Lambert’s ‘primary research focus is on maritime history, especially the study of maritime communities, merchant shipping, and naval logistics c.1300-c.1600’. He is the author, co-author, and co-editor of several academic works on these subjects, including Agincourt in Context: War on Land and Sea (Routledge, 2018), Military Communities in Late Medieval England: Essays in Honour of Andrew Ayton (Boydell & Brewer, 2018), and Shipping the Medieval Military: English Maritime Logistics in the Fourteenth Century (Boydell & Brewer, 2011).

Steven Mentz is Professor of English at St. John’s University in New York City. In his own words, Professor Mentz’s research focuses on ‘Shakespeare, 16th and 17th-century English literature, environmental humanities, ecocriticism, [and] oceanic culture’. He is the author of several academic books on these subjects, including Ocean (Bloomsbury, 2020), Break Up the Anthropocene (University of Minnesota Press, 2019), and Shipwreck Modernity: Ecologies of Globalization, 1550 – 1719 (University of Minnesota Press, 2015), and the editor or co-editor of Oceanic New York (Punctum Books, 2015), The Age of Thomas Nashe: Text, Bodies and Trespasses of Authorship in Early Modern England (Routledge, 2014) and Rogues and Early Modern English Culture (University of Michigan Press, 2004).

Along with Claire Jowitt, Professor of Renaissance Studies at the University of East Anglia, these two scholars are also co-editors of a new edited volume, The Routledge Companion to Marine and Maritime Worlds, 1400-1800, published this year. About three weeks ago, Chase spoke with Craig Lambert and Steven Mentz over skype about this new volume, discussing topics including how the book situates itself in scholarship on the late medieval and early modern oceans, the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in writing about the sea, and the significance of the period 1400-1800 in the history of maritime worlds. Listen on to find out more.

If you have any thoughts, questions, or comments about this episode, or would like to pitch us an idea for a new episode, feel free to email us at theglobalhistorypodcast@gmail.com, or send us a message on our website’s contact form, facebook, twitter, or instagram. If you would like to consult further resources on global history, feel free to visit our ‘Further Resources‘ page.

IMAGE 1: In what ways does this new volume challenge ‘chauvinism’ and narratives of ‘European mastery’ of the oceans? Portrait, ‘An aged Vasco da Gama, as Viceroy of India and Count of Vidigueira’, from the c. 1565 compendium, Livro de Lisuarte de Abreu. Pierpont Morgan Library, M.525, downloaded from Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

IMAGE 2: What role does the idea of ‘heroism’ play in maritime history? Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, Portrait, ‘Sir Francis Drake wearing the Drake Jewel or Drake Pendant at his waist’, 1591. Height: 116.9 cm (46 in); Width: 91.4 cm (35.9 in). Medium: oil on canvas. Accession Number: BHC2662. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Caird Collection, downloaded from Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

IMAGE 3: How can scholars use cartography to write global maritime histories? Describing the West-India Navigation, from Hudson’s Bay to the River Amazones… (London: Mount and Davidson, 1794), Book 4, 1794 edition. Dimensions: Object Height: 48 cm; Object Width: 81 cm. Scale: 1: 5,700,000. List Number: 12434.067. Pub List Number: 12434.000. Image Number: 12434067.jp2. David Rumsey Historical Map Collection. © 2000 by Cartography Associates. Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0).

IMAGE 4: In what ways does cartography reveal the ways in which the sea was a space of cultural encounter? Northern Indian Ocean, in Atlas nautique du Monde, dit atlas Miller, 1519, fol. 3r. Notice n° : FRBNF40887480. Description from the World Digital Library: “The map presented here is from the Miller Atlas in the collections of the National Library of France. Produced for King Manuel I of Portugal in 1519 by cartographers Pedro Reinel, his son Jorge Reinel, and Lopo Homem and miniaturist António de Holanda, the atlas contains eight maps on six loose sheets, painted on both sides. The maps were richly decorated and illuminated by António de Holanda, a Dutch native who had been in Portugal for nearly ten years. … For other parts of the world about which Europeans still had limited knowledge, geographic details are drawn from the cartographer’s imagination or informed by views that originated with Ptolemy. One side of the map (folio 3 recto of the atlas) shows the Northern Indian Ocean with Arabia and India. The equator is shown; other features include the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Persian Gulf, Ganges Delta, and the Nicobar Islands. … Both sides of the map have ornamental gold leaf, red banners with gold lettering for place-names, heraldic shields and flags, and vessels flying either the Portuguese Cross of the Order of Christ or the Ottoman crescent…” Bibliothèque nationale de France, downloaded from the World Digital Library.

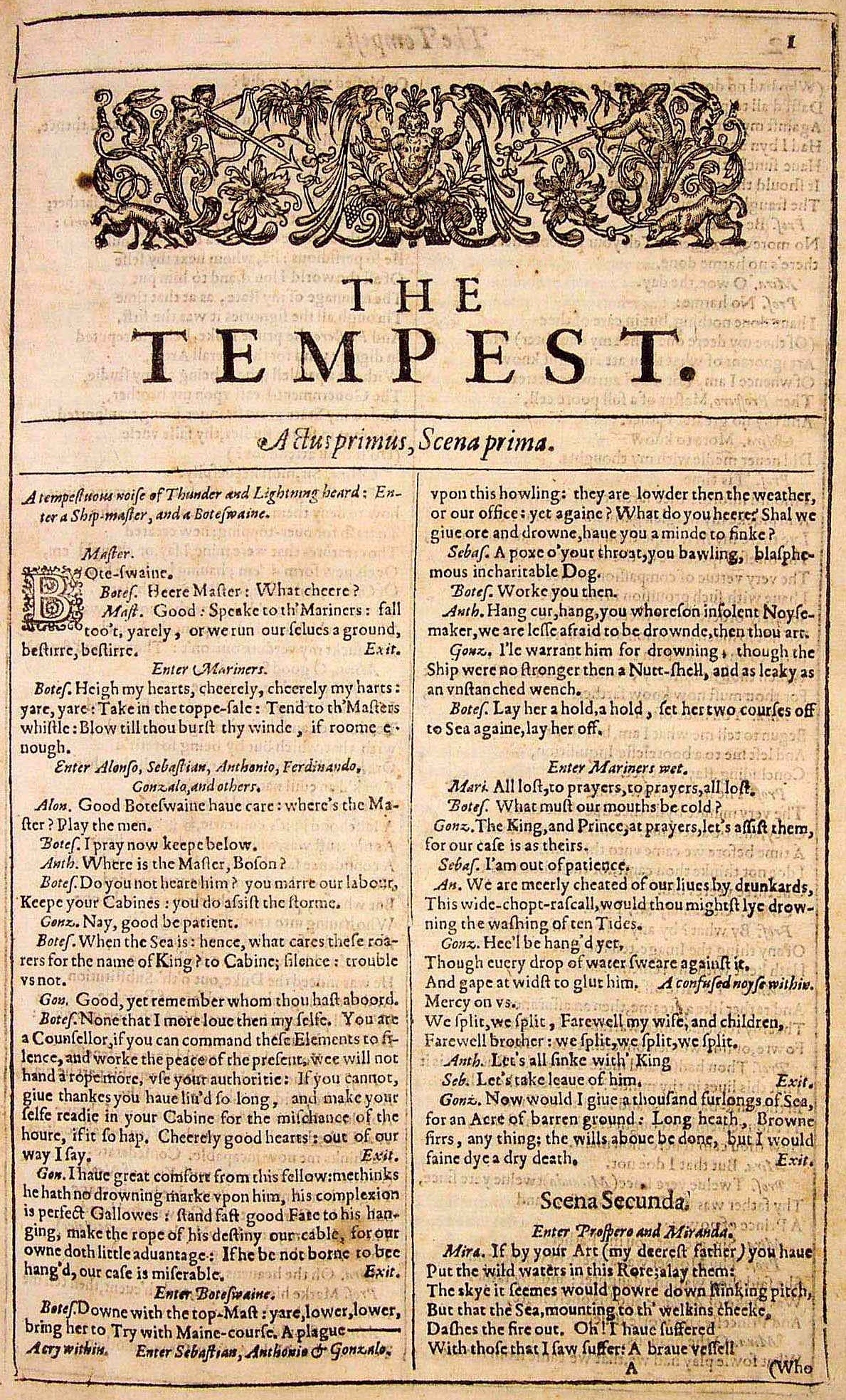

IMAGE 5: What can sources like poetry and plays tell us about how early modern people conceived of their relationship with the seas? Title page, William Shakespeare, The Tempest, from the 1623 ‘First Folio’. The Internet Shakespeare Editions, downloaded from Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

IMAGE 6: Early modern port cities like London were important centers of global trade. ‘Bird’s eye view of the City of London from Hampstead to St. Dunstan in the East’, 1600. Engraving. After John Norden. Downloaded from Barrie Cook, ‘Historical city travel guide: London, late 16th century’, 10 July 2020, The British Museum Blog.

IMAGE 7: Manila offers a good example of a port city in Asia where individuals from diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds mingled. Detail of the city of Manila from the ‘Carta hydrographica y chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas : dedicada al Rey Nuestro Señor por el Mariscal d. Campo D. Fernando Valdes Tamon Cavallo del Orden de Santiago de Govor. Y Capn’. Contributors: Pedro Murillo Velarde and Nicolás de la Cruz Bagay. Manila, 1734. Description: “Relief shown pictorially. Shows names of coastal towns and historical sailing routes. In lower portion of map: Le esculpio Nicolas de la Cruz Bagay … 1734. Includes text, descriptive notes, ancillary maps of Guam, cities of Manila, Cavite, and Zamboanga, and illustrations depicting episodes from the daily life of different peoples on the islands.” Call Number/Physical Location: G8060 1734 .M8. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C.

IMAGE 8: Lisbon was an important early modern port city. View of Lisbon, in Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg, Civitates orbis terrarum (Cologne, 1572), vol. I. Downloaded from Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

IMAGE 9: What would it have felt like for a Dutch sailor to arrive in the port city of Malacca in the Malay Peninsula in the seventeenth century? ‘De stad Malacca: Dutch Ships in Malacca Harbor’, in Wouter Schouten, Oost-Indische Voyagie, Tome III (1676), p. 376. Etching, copper plate. Downloaded from Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

IMAGE 10: Potatoes were an important plant which crossed the Atlantic from the New World in the early modern period, as part of the ‘Columbian Exchange’. John Gerard, The Herball, or, Generall historie of plantes (London: Imprinted by John Norton, 1597). Description: “There had been an earlier written description (but with no illustration) of the plant in Gaspard Bauhin’s Phytopinax of 1596. The Dibner Library of the Smithsonian Libraries has this first edition. The Biodiversity Heritage Library has digitized the copy in the Peter H. Raven Library, Missouri Botanical Garden”. Downloaded from Julia Blakely, ‘Celebrate the Potato’, 12 September 2016, Smithsonian Libraries Blog: Unbound.

IMAGE 11: To what extent were early modern states able to exercise authority over the seas? Anonymous English School, ‘English ships and the Spanish Armada’, 16th century. Medium: oil on poplar panel. Dimensions: Frame: 1380 mm x 1700 mm x 110 mm; Painting: 1120 mm x 1435 mm. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, downloaded from Wikimedia Commons. Artwork: Public Domain. Descriptive Information: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0 license.

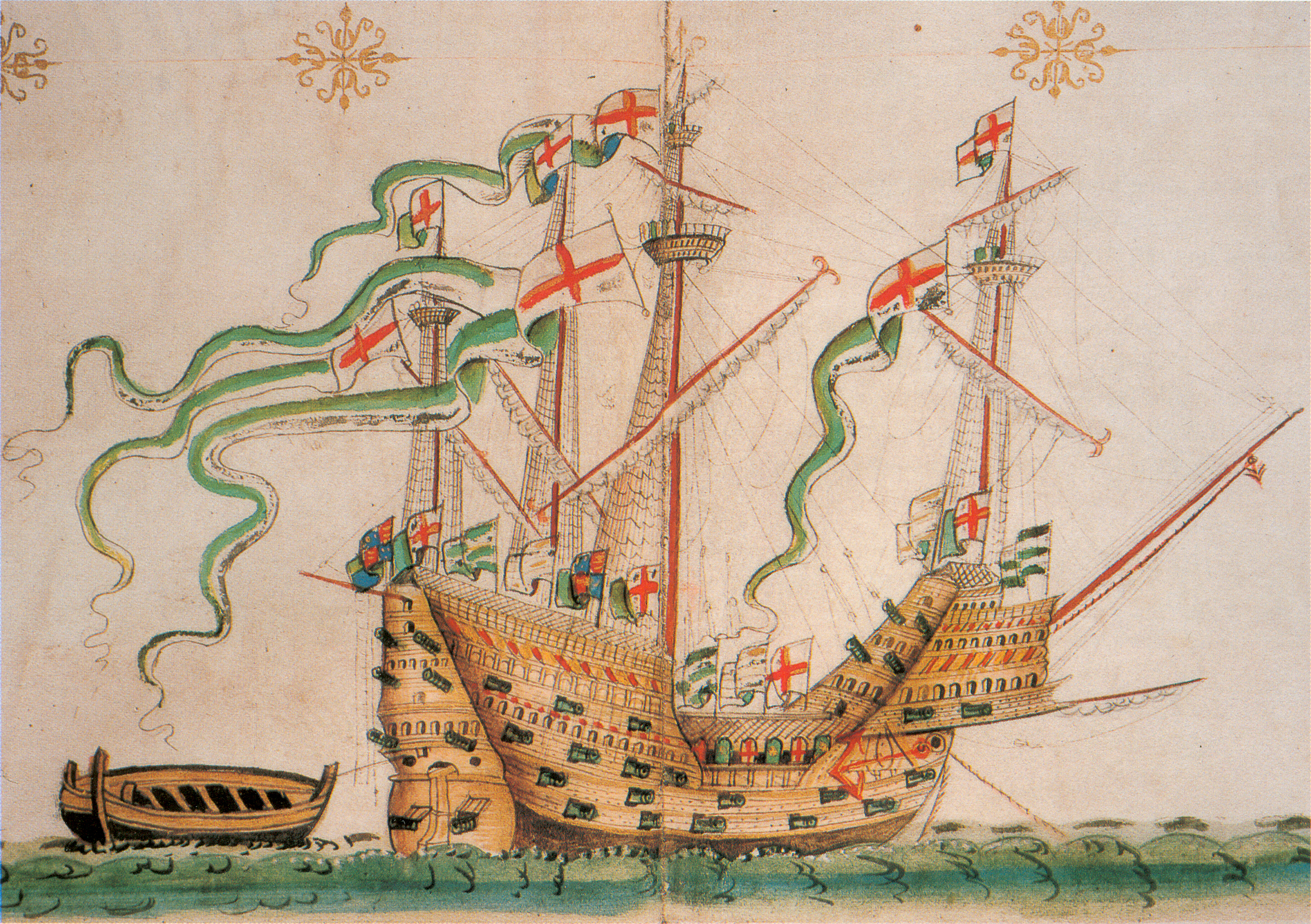

IMAGE 12: In what ways were ships important spaces of encounter, violence, and knowledge-making in the early modern world? ‘Illustration of the carrack Peter Pomegranate, also known as the Peter‘, ca. 1546, from the ‘Anthony Roll’ as reproduced in C. S. Knighton and D. M. Loades (eds), The Anthony Roll of Henry VIII’s Navy: Pepys Library 2991 and British Library Additional MS 22047 With Related Documents (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2000), p. 42. Photograph: ‘Own scan. Photo by Gerry Bye. Original by Anthony Anthony.’ Downloaded from Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

IMAGE 13: To what extent was the early modern sea characterized by violence? ‘[An anonymous] 16th century Portuguese illustration depicting the Nautaques – fishermen who inhabited the shores of eastern Persia and around the mouth of the Indus and frequently attacked tradeships, including Portuguese ones. The inscription reads: “Noutaques are thieves who go robbing over the sea.”‘ Album di disegni, illustranti usi e costumi dei popoli d’Asia e d’Africa con brevi dichiarazioni in lingua portoghese, ca. 1540. Biblioteca Casanatense, Rome. Downloaded from Wikimedia Commons.

IMAGE 14: What are the challenges and opportunities of reconstructing indigenous peoples’ perspectives of the sea and of European engagement with their cultures? Tupaia, ‘Longhouse and Canoes in Tahiti’, in Drawings, in Indian ink, illustrative of Capt. Cook’s first voyage, 1768 -1770, chiefly relating to Otaheite and New Zealand, by A. Buchan, John F. Miller, and others. Large Folio. Bequeathed by Sir Joseph Banks, Bart. Created: 1769. Format: Pen and Indian Ink, Watercolour, View. Creator: Tupaia. Description: “Tupa’ia, a navigator and priest from Raiatea, assisted Captain James Cook on his first voyage to the South Pacific (1769–71). The drawing shows a traditional longhouse in Tahiti situated on a beach fertile with different types of trees and plants (pandanus, breadfruit, banana, coconut and taro can all be identified). In the foreground three canoes are being navigated by local men. The double-sailed vessel on the left is a sailing canoe and the other two boats are used for war. The bow and stern of each war canoe is decorated with a wooden ‘tiki’ sculpture (a carved image of a god or ancestor). Warriors armed with spears stand on platforms raised from the sterns of both vessels ready for battle.” Shelfmark: Add MS 15508. Held by © British Library.

IMAGE 15: Forms of sea travel were diverse around the world, revealing the deep and varied ways in which different societies engaged with the sea. Description: ‘Indigenous Australians in bark canoes, drawing by Tupaia’. Published: 1770. Format: Drawing. Creator: Tupaia. Description: “Tupaia’s drawing shows two canoes, in one of which a man is using a three-pronged spear to catch a fish. Banks described how, as the Endeavour entered Botany Bay, he observed ‘four small canoes’ under the southern headland: ‘In each of these was one man who held in his hand a long pole with which he struck fish, venturing with his little imbarkation almost into the surf. These people seem’d to be totaly engag’d in what they were about: the ship passd within a quarter of a mile of them and yet they scarce lifted their eyes from their employment.'” Shelfmark: MS 15508 f. 10. Held by © British Library. Public Domain.

IMAGE 16: How did Europeans view non-European societies, for example, through their ships? William Hodges, ‘Tahitian War Canoes’, in A COLLECTION Of large Drawings in Indian ink, made by Wm. Hodges, during the second voyage of Capt. Cook, in 1772-1774, viz., Fayal; -Tonga Tabu or New Amsterdam;-Mallicolo;-Resolution Harbour, in St. Christina, one of the Marquesas;-Savage Island;- Sandwich Island;-Alietea;-War Canoes of Otaheite ;-Otaheite; New Caledonia. Created: 1774, Tahiti. Format: Drawing. Creator: William Hodges. Description: “William Hodges made these drawings of Tahitian war canoes during James Cook’s second voyage. One shows a fleet drawn up on shore at Pare, home of Tahitian chief Tu. Although ostensibly preparing for an expedition against the neighbouring island of Mo‘orea, the display was probably also intended to impress the British, and to help to form an alliance.” Shelfmark: Add MS 15743 f.8. Held by © British Library. Public Domain.

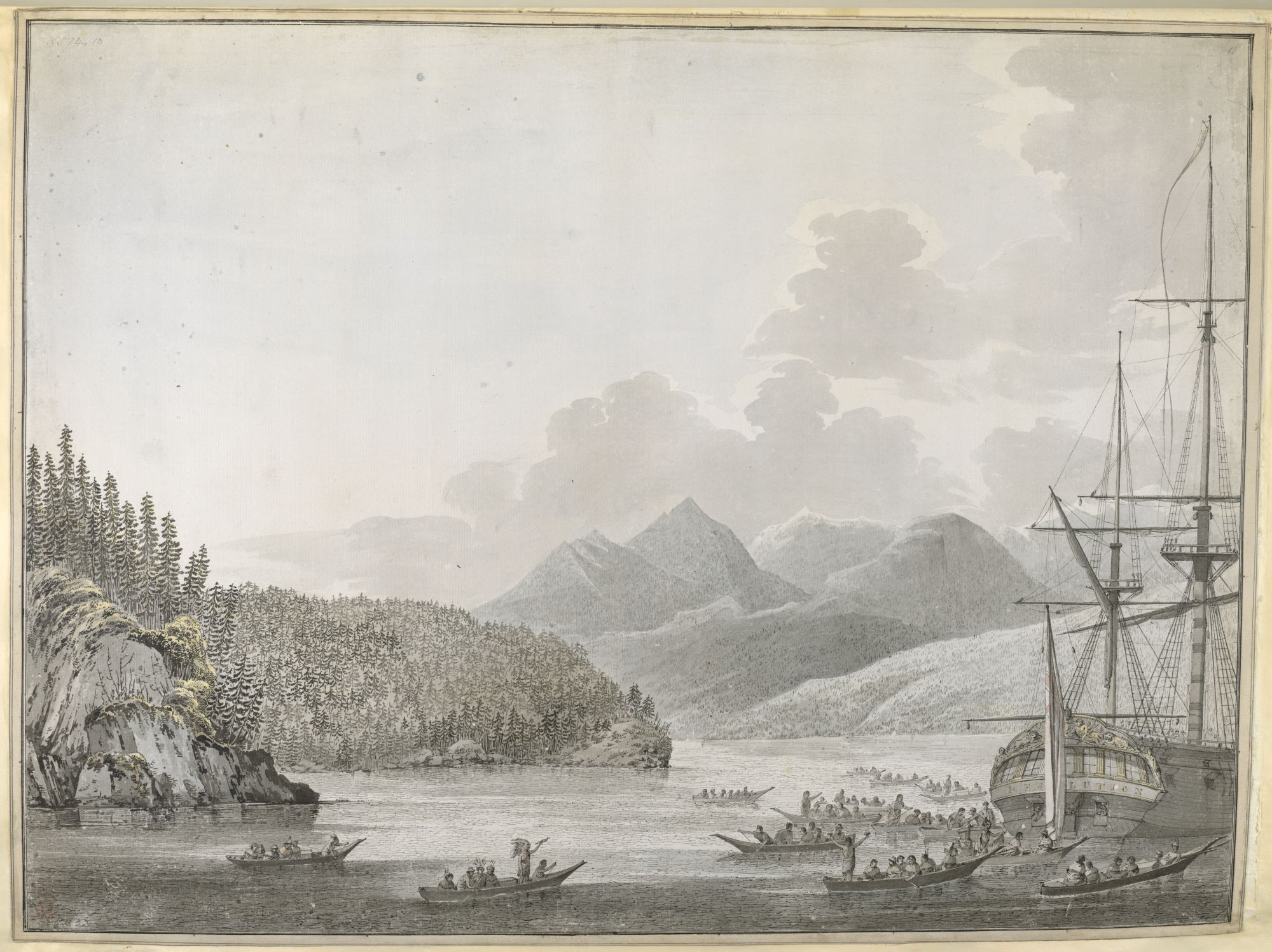

IMAGE 17: To what extent was cultural encounter, as manifested through the arrival of a ship in a new location, a ‘performance’? John Webber, NINETY drawings, some in Indian ink, some colored, executed by J. Webber, during the third voyage of Captain Cook in the South Seas, in the years 1777-1779 ; contained in two large Portfolios. Presented, in 1843, by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty. Created: 1777-78. Format: Pen and ink, watercolor, view. Description: “The views made during Captain Cook’s third expedition are John Webber’s best-known works. After being spotted by the famed botanist, Daniel Solander, who recommended him to the Admiralty, Webber was given the task of compiling a visual record of the voyage of the Resolution and the Discovery from 1776–80. A number of the drawings were later engraved and published in A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean in June 1784. … Cook’s third voyage reached Nootka Sound in April 1778 while searching for the Northwest Passage. Webber’s view shows the native residents of Yuquot in canoes surrounding the Resolution.’” Shelfmark: Add MS 15514, f.10. Held by © British Library. Public Domain.

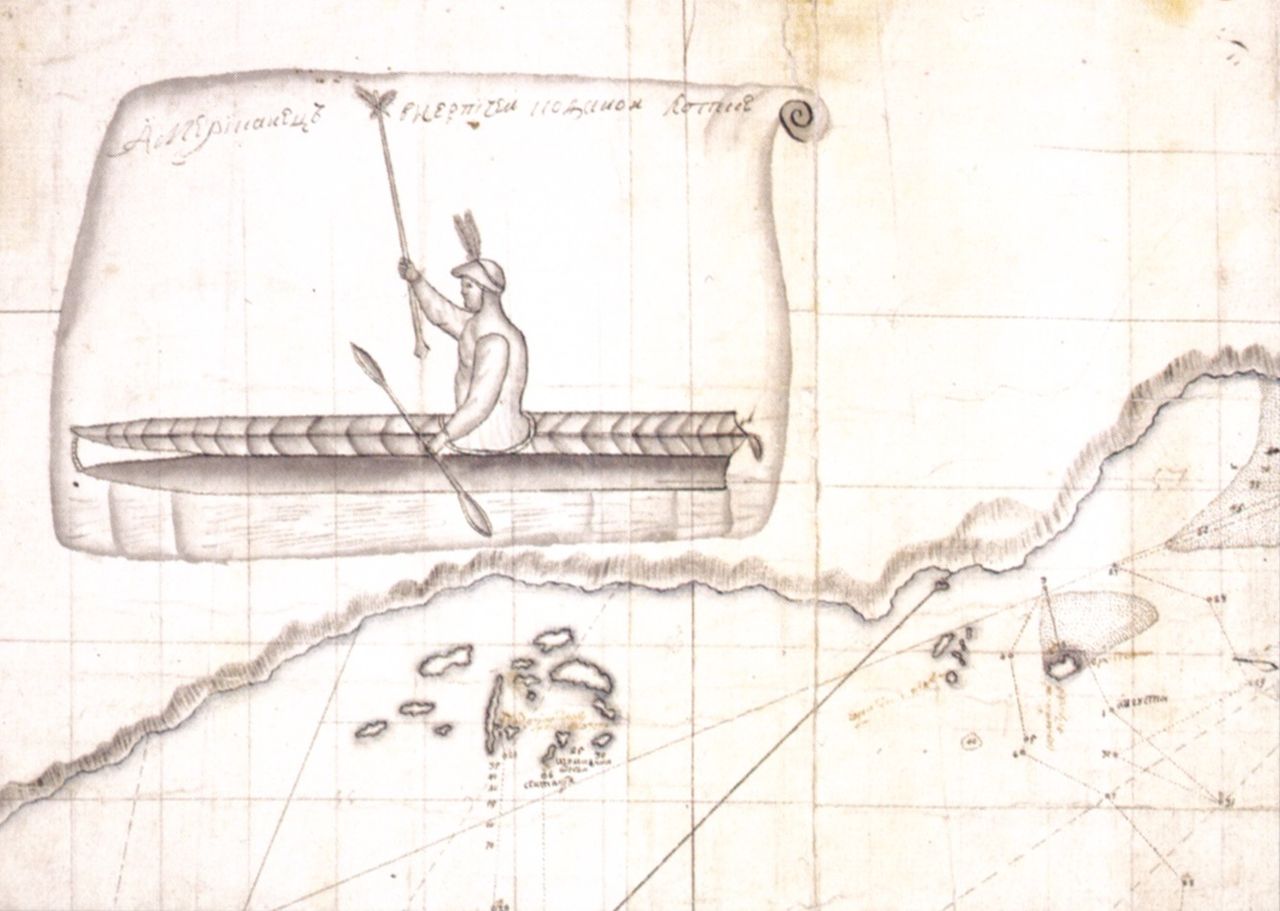

IMAGE 18: Sven Larsson Waxell, ‘Bering’s first encounter with Aleuts at Shumagin Island. Drawing by Sven Waxell, the mate of Bering’s ship St. Peter’, circa 1741. Downloaded from Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

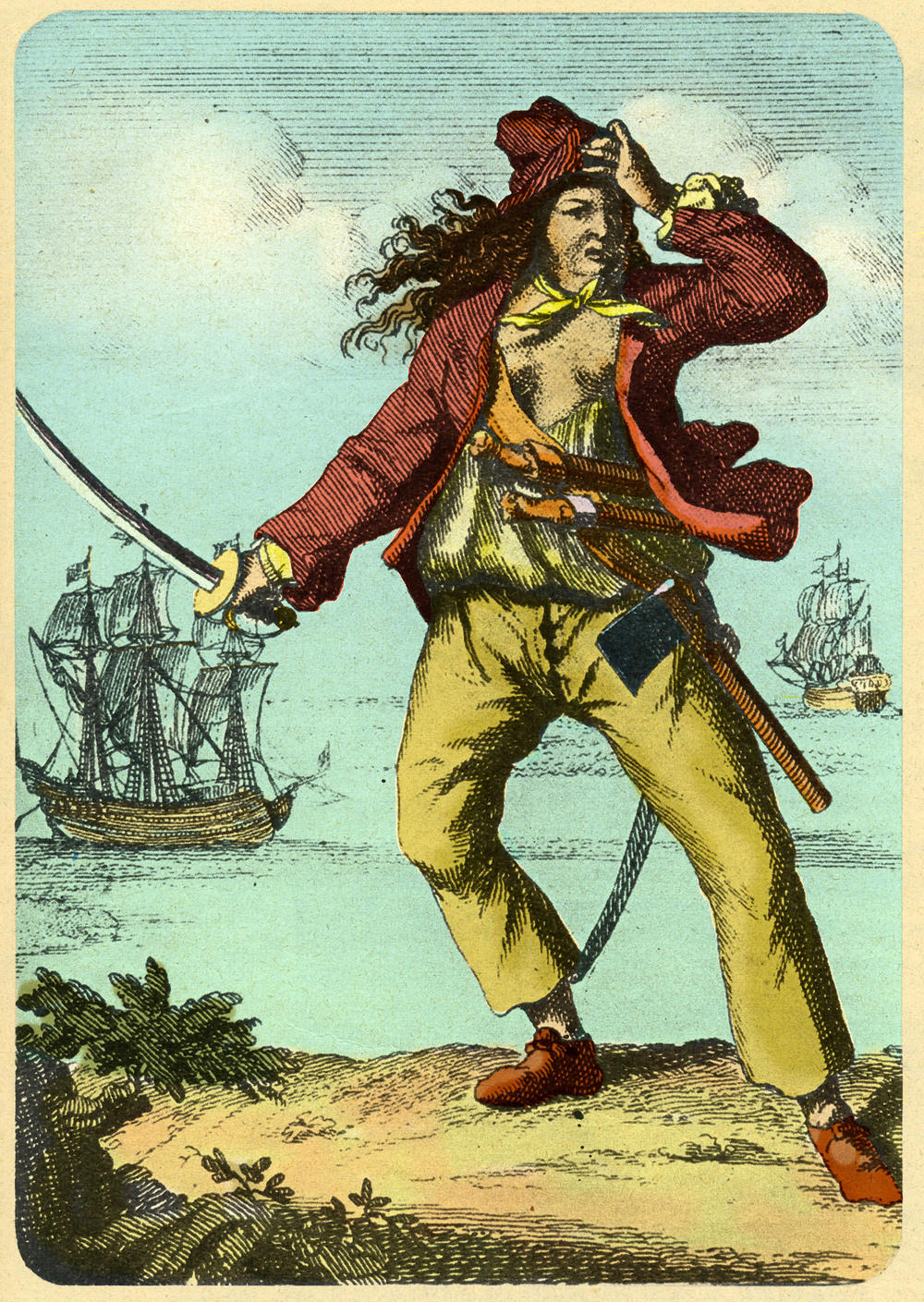

IMAGE 19: What are the challenges and opportunities of foregrounding women’s experiences of the sea in the early modern period? Mary Read (1690-1721). Engraving from A General History of the Pyrates (1725, 3rd edition?). Downloaded from Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

IMAGE 20: What were some of the challenges in keeping individuals healthy on long sea voyages? Title Page, Leonard Gillespie, Advice to the commanders and officers of His Majesty’s fleet serving in the West Indies on the preservation of the health of seamen (London: J. Cuthell, 1798). Physical Description: vii, 31 pages. The University of Leeds Library, downloaded from the Wellcome Collection. Public Domain.

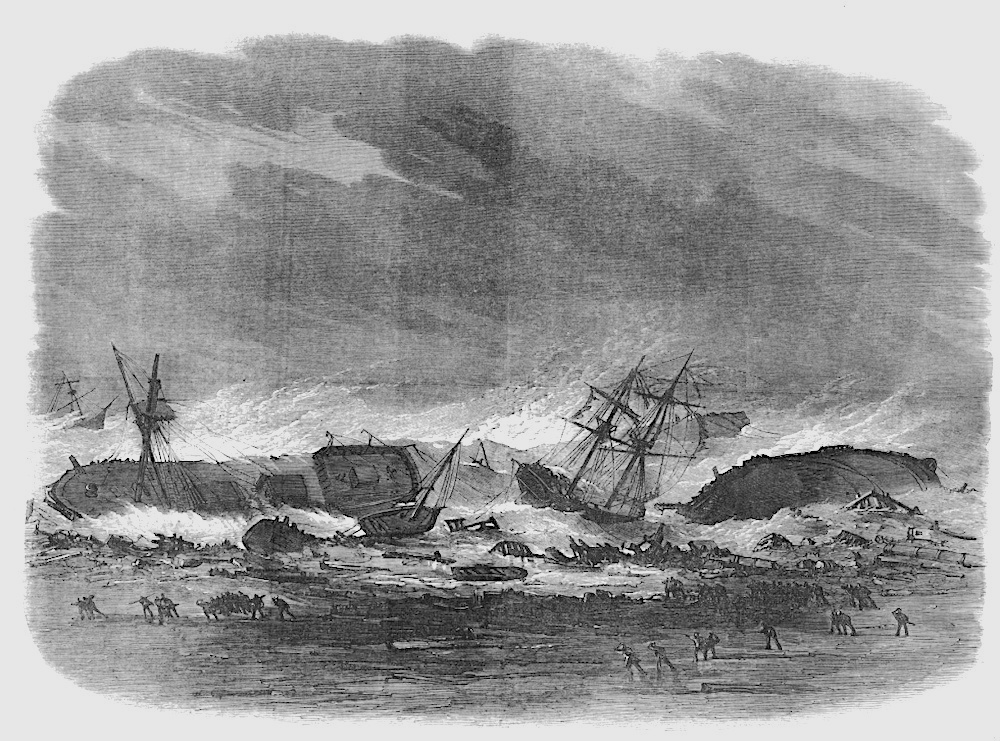

IMAGE 21: The sea could also be a space of potential despair, fear, and the unknown, as captured poignantly by the experience (and potentiality) of shipwreck. The Hurricane at Madras: Wrecks on the Beach, from the 8 June 1872 issue of the Illustrated London News. “Our Engraving is from a sketch by Mr. R. S. [F.] Chisholm…”, p. 557. Downloaded from The Victorian Web: Literature, History, & Culture in the Age of Victoria, which in turn downloaded the engraving and the accompanying article from “The Hurricane at Madras”, Illustrated London News (8 June 1872), 555. Hathi Trust Digital Library version of a copy in the University of Michigan Library. Web. 10 December 2015.

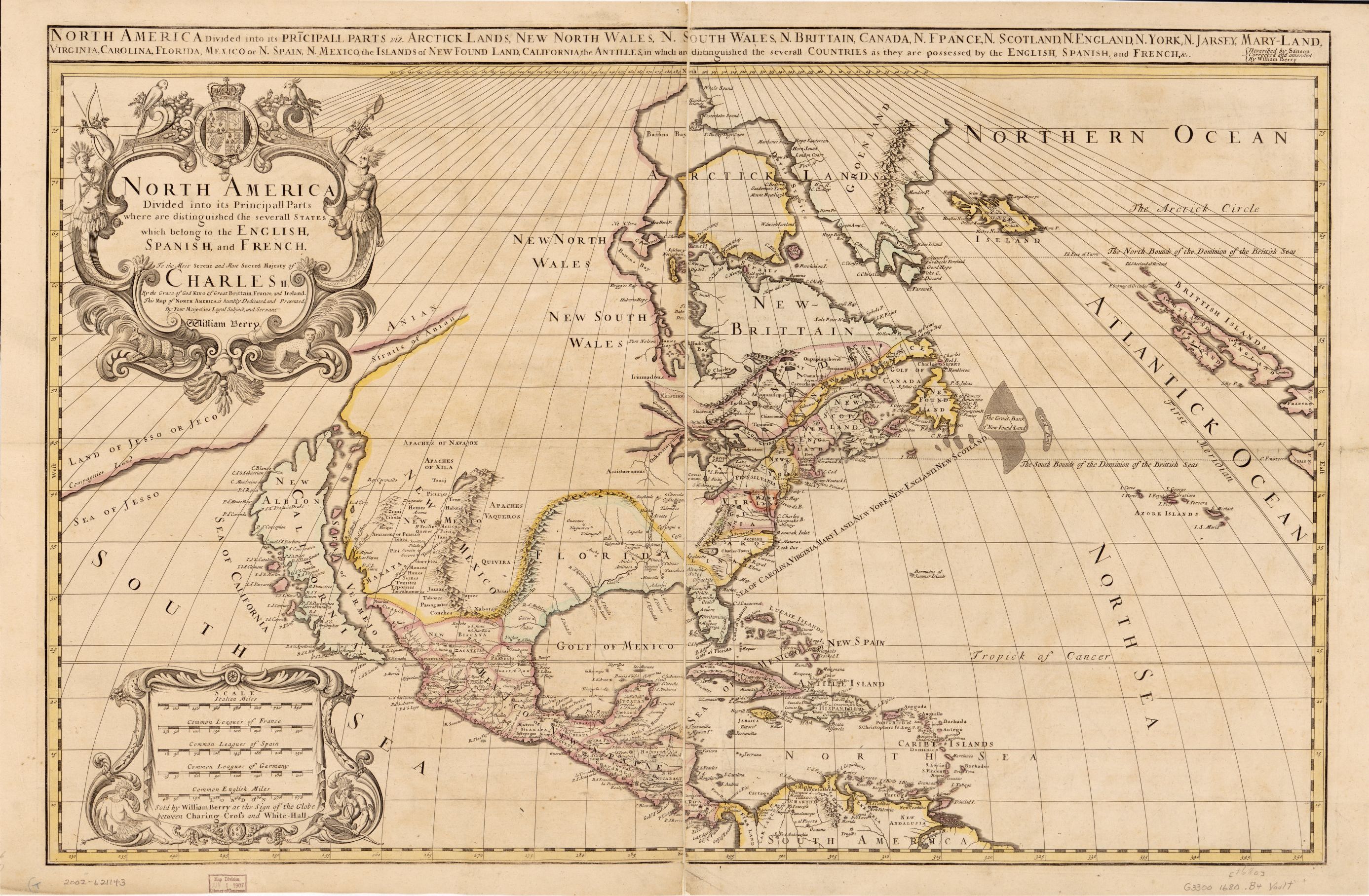

IMAGE 22: How does thinking from an oceanic perspective shed light on early modern globalization, and how does ‘oceanic thinking’ help to decenter the nation-state in historical analysis? ‘North America divided into its pricipall parts, viz. Arctick lands, New North Wales, N. South Wales, N. Brittain, Canada, N. France, N. Scotland, N. England, N. York, N. Jarsey, Mary-Land, Virginia, Carolina, Florida, Mexico, the islands of New Found Land, California, the Antilles, in which are distinguished the severall countries as they are possessed by the English, Spanish, and French, &c.’ (London: Sold by William Berry at the sign of the globe between Charing Cross and White-Hall, 1680). Description: “Relief shown pictorially. At upper right: Described by Sanson, corrected and amended by William Berry. Prime meridian: Ferro. Includes ill. Sectioned and mounted on cloth backing.” Medium: 1 map : hand col. ; 53 x 86 cm. Call Number/Physical Location: G3300 1680 .B4. Library of Congress Control Number: 2002621143. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C.

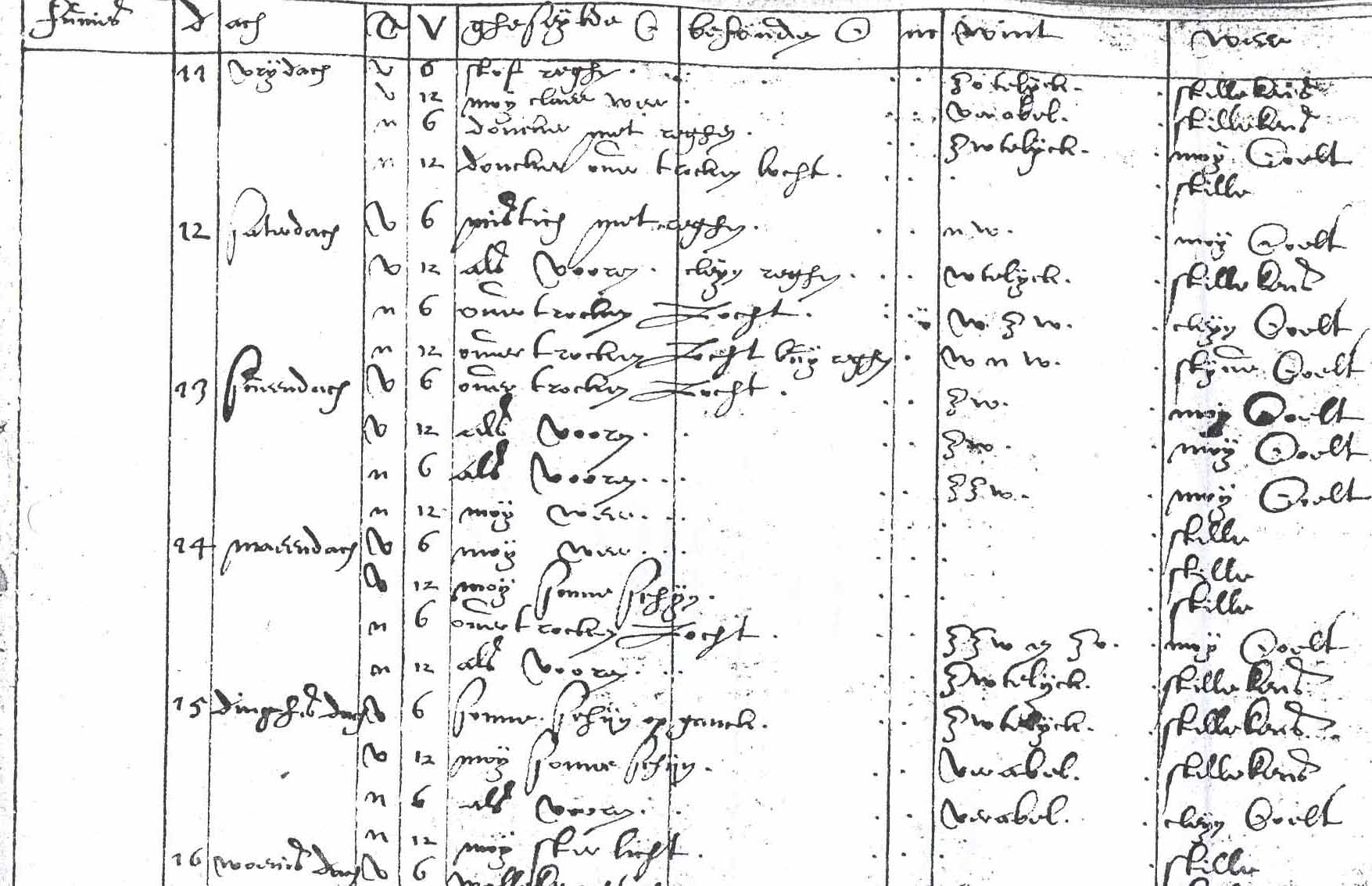

IMAGE 23: How can historical sources like ship logs shed light on the weather and climate of the past? ‘Part of a ships log kept by Philips Grimmaert on the ship Zeelandia, June 1599’. National Archives, The Hague, East India Company, no. 54, downloaded from Adriaan M.J. de Kraker, ‘Historical climatology, 1950-2006: An overview of a developing science with a focus on the Low Countries‘, Belgeo: Belgian Journal of Geography 3 (2006), 307-338 (Figure 1).

IMAGE 24: In what ways is the Black Lives Matter movement linked with the sea? ‘The empty pedestal of the statue of Edward Colton in Bristol, the day after protesters felled the statue and rolled it into the harbour. The ground is covered with Black Lives Matter placards.’ Photographer: Caitlin Hobbs. Created: 7 June 2020. Twitter, downloaded from Wikimedia Commons. CC BY 3.0 license.

One thought on “Craig Lambert and Steven Mentz on Approaches to Late Medieval and Early Modern Maritime Worlds”